FORT COLLINS — Researchers at Colorado State university are doing their part to help rid our atmosphere of greenhouse gasses with intense study into cattle. Everything from their feed to their genetics can make a difference.

Why cattle, you ask?

Their burps — or enteric methane, which is unused energy from an animal’s body and left over from eating — collectively have added up to 2% of the U.S.’s greenhouse gasses. While the rest of the country is on notice to start thinking about sustainability and their environmental footprints, cattle ranchers and producers also have a stake in coming up with solutions. Teams are studying diets, animal health, grazing and more.

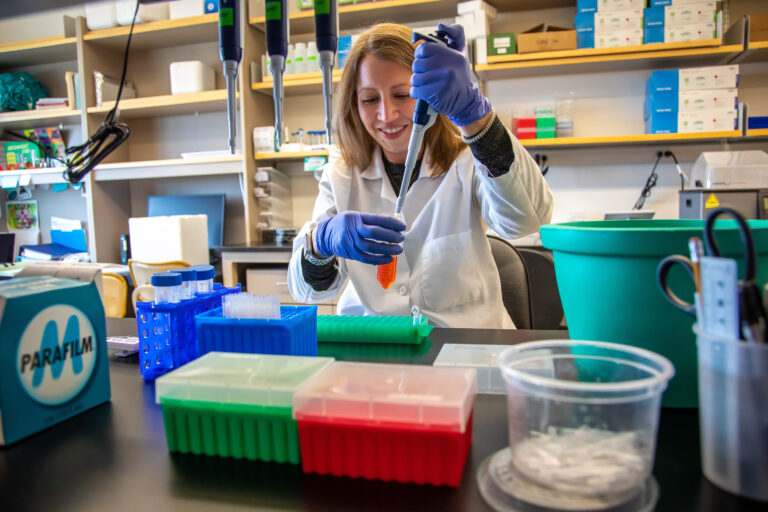

For Sara Place, an associate professor of feedlot systems, the work that she and her team does to not only measure enteric emissions from cattle but also to refine diets and to study genetics that could eventually lead to steers contributing less methane, helps all in the long run.

The program to measure cattle emissions got started in 2022 with the addition of a GreenFeed system into its Climate-Smart Research Facility at Colorado State University’s Agricultural Research, Development & Education Center. It is the largest in the country dedicated to measuring greenhouse-gas emissions in both grazing and feedlot systems, according to AgNext.

Cattle visit feeding boxes that deliver tasty alfalfa pellets for them to eat while the box measures their emissions and collects the data, which feeds the research. The system can feed up to 40 head of cattle at a time. The system measures carbon dioxide, methane, hydrogen and oxygen. Researchers can get enough information on their emissions output in 21-28 visits to the feeder. From here, they can test different components of their feed to determine any changes, without disturbing the cattle from their daily routines.

The genetics part is what excites Place the most, as it has a real-world component that can potentially guide breeding decisions that could help the producer.

“Hopefully, there is a component of how we select animals, about which bulls get used on an operation that could have an influence,” Place said. “That’s exciting and something that would still be a few years out.”

Studying enteric methane is about not only the environment, but also the animal’s health, and frankly better economics for producers. As an example, research already shows that feeding cattle a grain-based diet reduces methane emission by 40% from a 100% hay diet, Place said.

“There’s multiple potential benefits there. There are reasons cattle producers are interested in this,” Place said. “Yes, sometimes the motivation is, ‘Hey we’re getting questions on what we can do to mitigate emissions?’ And another big one, and it builds on diets, is that grain-based diets reduce methane emissions. We know it’s a loss of feed energy. The calories the cow eats gets lost in the atmosphere. So is there an opportunity to also improve feed efficiency or the ability to convert feed into beef?”

Finding that answer could result in cost savings to producers, Place said.

Such studies can help influence the entire life cycle of cattle: calves start out in a cow-calf operation, then are weaned at six months. They will then go through another grazing system for another five to six months on grass, then another grazing system before going to a feedlot after a year. There, for the last 180 days of their lives, they’re fed a high-grain diet, which “allows their beef to meet the American consumer expectation,” Stackhouse-Lawson said.

“If we’re able to improve calf health, for example, and they grow into healthy cows and become more productive and better utilize the feed, Sara’s group can develop enteric methane mitigations,” said Kim Stackhouse-Lawson, director of CSU’s AgNext Program. “So the animal is not just reducing her methane, but because she’s been more healthy, used less feed, water, and less time from a labor standpoint. Then our modelers can say that change in management that improved the health of the animal plus this mitigation resulted in these improvements related to economic improvements.

“We’re then really able to provide producers with a more granular understanding of how the system would respond to a practice they might adopt,” Stackhouse-Lawson said.

Author

-

Sharon Dunn is an award-winning journalist covering business, banking, real estate, energy, local government and crime in Northern Colorado since 1994. She began her journalism career in Alaska after graduating Metropolitan State College in Denver in 1992. She found her way back to Colorado, where she worked at the Greeley Tribune for 25 years. She has a master's degree in communications management from the University of Denver. She is married and has one grown daughter — and a beloved English pointer at her side while she writes. When not writing, you may find her enjoying embroidery and crochet projects, watching football, or kayaking and birdwatching on a high-mountain lake.

View all posts