DENVER — Research has shown that animals are good for your mental health. Merely petting a dog causes the release of dopamine and serotonin, and the mere presence of them can help with depression and anxiety.

This dynamic underpins the Institute for the Human-Animal Connection, which was established in the Graduate School of Social Work at the University of Denver in 2006.

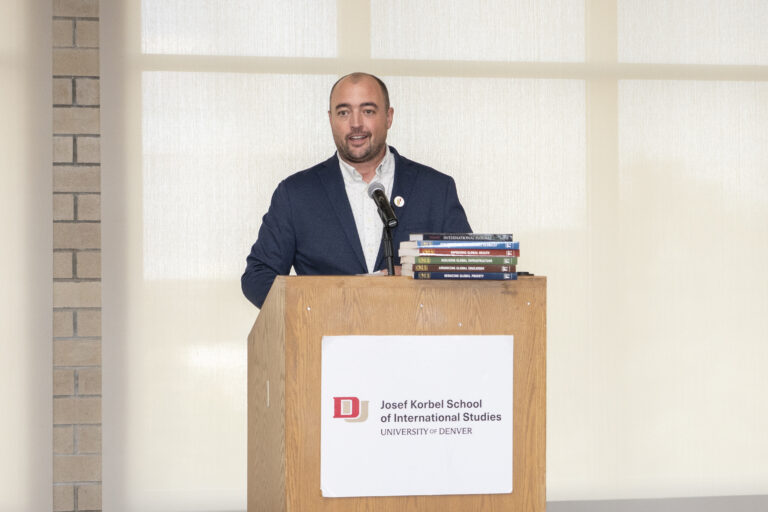

“It was started at the request of students to have a course in how to incorporate animals into social work,” said Kevin Morris, who has served as the executive director of IHAC since 2022. “This is unique in that it’s housed in a school of social work. There are other academic programs, but they tend to be housed in schools of veterinary medicine.”

A molecular biologist by training, Morris began working in the field of human-animal connection after moving out of cancer research in 2008. A “pivotal moment” came when he was treating advanced cancer patients in an FDA-approved clinical trial at a facility in Loveland during that previous career.

“I had two German shepherds at the time, and I used to always ask people when they signed up if it was OK if I brought the dogs,” Morris said. “One woman who was responding to the treatment refused treatment because my dogs, Buck and Roma, weren’t there that day. I asked, ‘Why?’ She said, ‘Because I can visualize them lying on their mats outside the door, and it keeps me calm while I’m being treated.’ And that just always stuck with me.”

The experience cemented Morris’ decision to use his research skills to work with animals, and he went full-time at DU in 2016 in large part due to IHAC. He now leads the institute with affiliated faculty Philip Tedeschi and Sarah Bexell, along with nine full-time staff members and about 20 graduate research assistants and interns.

The institute supports a master’s certificate called Human-Animal Environment Interactions and Social Work, the first of its kind in the country. “About a third of the students who graduate with their master’s in social work get that certificate, so it is a big draw here to this program,” Morris said.

DU also offers online certifications to professionals called IHACPro. About 1,500 professionals have used those certificate programs.

IHAC collaborates on programs with farm animals with Green Chimneys in New York, but much of the institute’s work is about the human-dog connection. One program involves prison inmates training dogs in Washington state. “The people who were in the dog-training programs had about a 15% lower recidivism rate than the people who hadn’t been in dog training,” Morris said.

IHAC also conducts research funded by animal-focused philanthropies such as Humane World for Animals and that is “more equity-focused,” Morris said. “The project we’re doing with PetSmart Charities is launching access to veterinary care programming with community partners all over the U.S.”

In Colorado, IHAC is investigating the impact of dogs on veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with SomaLogic Inc., a researcher at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and about a dozen service-dog training organizations in metro Denver, with funding from the Denver-based Morris Animal Foundation (no relation). The research builds on a 2024 study at IHAC concluding that dogs may support a more balanced stress response capacity.

“We are tracking both the veteran and their service dogs longitudinally with the veterans,” Morris said. “We’re getting a baseline PTSD diagnosis and then tracking the progress after they get their dog. And we’re also tracking the dogs. We’re tracking the dog’s behavior. We’re getting blood samples at different time points from both the veteran and their dog, and we will be using SomaLogic’s proteomic technology to do a deep dive into the biology of how the dogs reduce PTSD symptoms.”

SomaLogic’s technology allows researchers to gauge more than 10,000 biomarkers in the blood of the veteran and the dog. “We launched data collection at the end of last year, and we are on track to run a pilot study of the first 10 participants and their dogs at the end of this year,” Morris said. “The full study is 50 pairs of veterans and dogs tracked over a year, so we’ll collect data before they get matched, a month after, six months after, and at 12 months after.” If all goes as planned, data collection could be complete by the end of 2027.

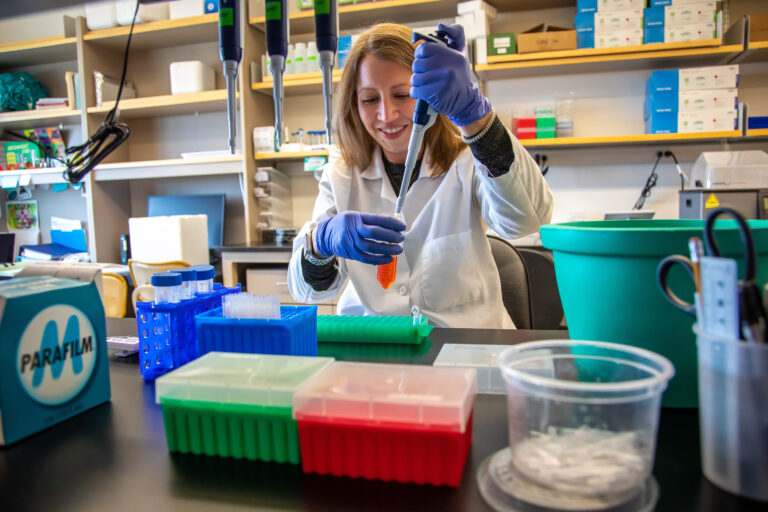

Jaci Gandenberger, a research associate with IHAC, began working for the institute as a graduate student in 2017, then went full-time when she completed her degree in 2019. “I’ve really fallen in love with how IHAC looks seriously at a lot of the most pressing issues we’re all facing today, and how our relationships with other animals can hopefully help us address some of those issues,” she said.

“My role on the project is really bringing a lot of the social work angle and some of that background,” Gandenberger said. “Kevin brings the biology and I do a lot of recruiting of potential participants, coordinating with service dog organizations, and handling a lot of the logistics around getting blood draws from around the country.”

Gandenberger said that many veterans she’s met through IHAC were visibly tense before being matched with service dogs. “After they get their dogs and they settle in, they’re checking in and sending photos,” she said. “They’re telling stories of them just playing and being silly with their dog.”

Gandenberger said she’s also seen service dogs help foster post-traumatic growth, a positive psychological change experienced by some PTSD patients, in some veterans. “Having that dog with you can help make the world feel just a little bit safer,” she said. “You’ve got a buddy, you’ve got support, and so you can go out, you can make those connections, and maybe that’s what helps get you to that place.”

As client services coordinator for Englewood-based Freedom Service Dogs, Kaity Brookes is the point of contact for some of the veterans who are enrolling in the pilot study. Brookes interned with IHAC from 2021 to 2022 while working on a graduate degree in social work at DU.

Working at Freedom Service Dogs “has been a continuation of the work that I’ve done with IHAC since I worked on that foundational study surrounding stress and animals,” Brookes said. “I’m really excited for this new study that they’re doing, so we’ll be able to have some quantitative evidence of service dogs providing benefits for individuals with PTSD.”

Brookes said she’s observed numerous positive outcomes in her three years with the organization, and the research could broaden that impact. “Currently, there is a lot of redlining that’s happening with PTSD service dogs and whether or not they are deemed necessary for veterans,” she said. “Having true quantitative evidence of the legitimate success of service dogs could potentially open the doors to proving the necessity of these dogs for veterans.”