Hovering around $600,000 in 2025, the median home price in Colorado has skyrocketed in recent years.

While that number now places Colorado in the top 10 most expensive markets in the country, the problem is far from local. The National Low Income Housing Coalition estimates that the United States has a shortage of 7.1 million affordable rental units nationwide.

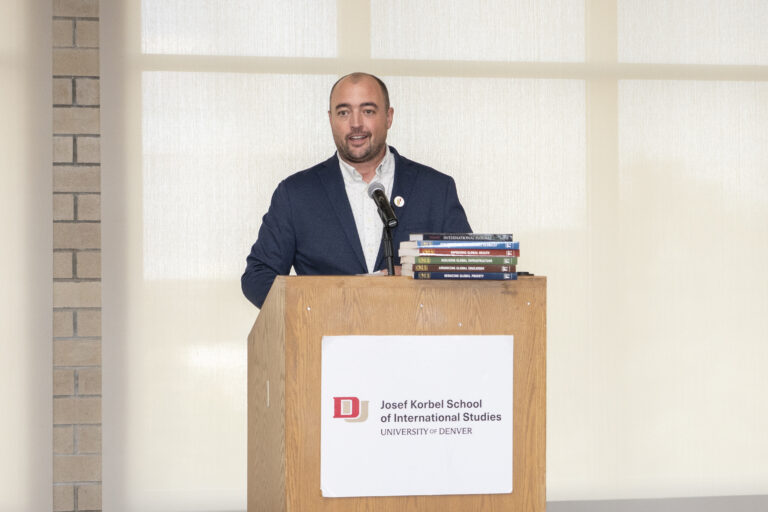

Eric Holt, associate professor of the practice at the Franklin L. Burns School of Real Estate and Construction Management at the University of Denver, has focused his research on the issue.

Holt, who joined DU in 2016 after 35 years in the construction industry, described “two camps” with different approaches to housing affordability issues. “There are people that are huge into technology, and say that AI, 3D printing, and a whole bunch of technology is going to save housing. Then there are a whole bunch of people in the workforce development side of it. I try to keep my feet into both camps, just to see who’s doing what and where things are going.”

Holt recently completed a study on workforce challenges in collaboration with the Home Builders Institute. “We’ve been talking about labor shortages since the crash of 2006 to 2011, but no one had really quantified it,” he said. “We interviewed 30 homebuilders across the nation, and had a whole list of questions about how labor shortages have impacted their timeline, their cycle time, their costs, and where they see the future going. Then we compiled all that and put out a report to HBI and the public.”

In June, the National Association of Home Builders expanded on the research. “Dr. Robert Dietz, their chief economist, took our data and was able to extrapolate out the actual impact of how many units don’t get built a year, the dollar amount that we’re losing, and the time amount we’re losing,” Holt said.

The final report estimated that the labor shortage had a negative economic impact of $10.8 billion per year due to longer construction times associated, and that it led to 19,000 homes not being built in 2024 alone.

Holt said Colorado is a microcosm of the national issues. “What’s unique about Colorado is everything we have going on here — climate issues, labor issues, cost issues — we are a reflection of the rest of the industry,” he explained. “Certain parts of the nation have very specific regional issues. California has some of the highest labor rates and is one of the most regulated states. We don’t deal with coastal issues or hurricanes like Louisiana, Florida, and the East Coast, but what I love about Colorado is when we study stuff in Colorado, it can apply nationally.”

One of Holt’s current projects is focused on a disconnect with Colorado’s construction workforce. The study is being conducted in collaboration with BuildStrong Academy.

“We have all these students that are graduating, but there’s a gap right now. Why aren’t they getting hired?” Holt said. “The old ways of career fairs and how people made connections pre-COVIC don’t seem to be effective anymore. Locally in Colorado right now, we’re looking at and interviewing students that have graduated from different programs, as well as builders, contractors, and other people that would be hiring those students, trying to figure out where the disconnect is.“

“Is it the student? They didn’t reach out, they didn’t follow up. They’ve got the skills, they know how to swing a hammer, but they don’t know how to network and interview. Or is it the builders now? Is it the industry that has changed how they hire?”

The project will interview about 30 students and 30 builders in fall 2025, and deliver a report around year’s end, Holt said.

Building codes are another contributor to higher housing prices, and Colorado is a national trouble spot. “The building codes in Colorado surprised me, moving here from Indiana,” Holt said. “I still do a lot of consulting with builders there, and they complain about the permit process taking two weeks and costing $2,000. Then we come here to Denver and the permitting process for just a single-family home could be 10 months or longer, with impact fees and everything else costing $50,000.”

Those could be changed, and Holt said he favored a statewide code. “Builders can’t build the same house across the street if it’s in a different jurisdiction without changing a myriad of little things that add up in cost,” he explained.

These issues make it difficult for homes built offsite in factories to gain traction in Colorado. “Fading West Development, or any of the other modular homes factories that are popping up around Colorado, they have 300 different authorities having jurisdiction, 300 different little tweaks they have to do to their boxes depending on where they’re going to go,” Holt said. “In a factory setting, you gain efficiency by building the same thing over and over again, like in a car. If we can’t do that because we don’t have a state code, that really is frustrating for builders, and it adds cost.”

Climate- and snow-based code changes are understandable, he added, but “some of these other code differences from jurisdiction to jurisdiction don’t make sense.”

Gracy Weil, a graduate research assistant at the Burns school, is working on research with colleague Bill Ray to illuminate some of the issues associated with building codes. Weil and Ray presented their most-recent study on code fragmentation at the Colorado Department of Local Affairs’ Housing Consortium in March 2025.

Weil noted that different Colorado municipalities use different iterations of IRC and IECC code. “If you’re working in 2008 code years in Morrison and have to make whole new plans for 2021 code years in Denver, that’s a lot of extra cost, it’s extra effort, and then it’s also extra time.”

That segued into Weil and Ray’s current research project on costs driven by construction delays. The work involves case studies of different municipalities and data-driven analyses to “really see what that affordability gap is, and how many people are getting priced out just from it taking too long,” said Weil, noting that Colorado could take cues from other states that have streamlined their entitlement processes. “So many more aspects of the entitlement process can be made administratively.”

The minutiae of building codes and permitting processes aside, there are also local cost catalysts that can’t be controlled. “We can’t change the fact that we sit on expansive soils,” Holt said. “You have to prepare the lots for any construction. That’s very unique to Colorado.”

It can add $50,000 for a single Denver lot. “It’s a pretty significant chunk of change,” Holt said. “On the Front Range, there are certain pockets that don’t have to do it, but those seem few and far between.”

In the end, the soil is just one of the variables driving the high cost of housing in Colorado. Holt said his research is about understanding the issue, but solutions remain elusive. “We’re really good in academia to tell you how hard it’s raining, but I don’t have a good way for you to build an ark yet,” he said.

Eric Holt is leading a free, in-person session at DU on Wed. Nov. 5, 2025 titled The High Price of Home: Unpacking Colorado’s Housing Affordability Crisis.