DENVER — For Corinne Lengsfeld, vice provost for research and graduate education at the University of Denver, the launch of the Colorado National Wastewater Surveillance System Center of Excellence was akin to building the plane after takeoff.

“During COVID, universities and cities decided to start testing wastewater as a de-identified, cheap way to measure the prevalence of disease,” said Lengsfeld, who holds a Ph.D. “DU did that, and we brought it online within seven days from the decision to do it to actually getting results.”

When students returned to DU in September 2020, the system was in place. “It proved to be a very helpful technique on campus to help manage case loads in dorms in a cost-effective way,” Lengsfeld said. “We actually caught a huge outbreak using it within two weeks. … We were able to contain that outbreak really, really quickly. It could have spread all across campus. It was just in one part of the dorm, and we were able to contain it in just under a week.

“It was revolutionary for me as a scientist to understand how you can use pretty untested concepts and learn quickly on the fly to implement them for successful public health interventions. It was actually a proud moment for me and the COVID team on campus, but also it was a moment where basic science actually had an immediate impact.”

Lengsfeld soon connected with Allison Wheeler, manager of the Wastewater Surveillance Unit at the Colorado Department of Public Health and the Environment. “She [Wheeler] and a lot of other professionals around the state of Colorado were also starting to work with wastewater utilities to do some similar things,” Lengsfeld said. “From that, a pretty cool friendship developed. We would meet and give each other emotional support in the heat of the battle once a month. That turned out to be scientifically really innovative in terms of idea-sharing and learning, as well as absolutely necessary to remain sane over time.”

From the dorms at DU, the program expanded to other residential facilities, then wastewater utilities. Wheeler ultimately applied for funding from the Center for Disease Control in 2021, then won a second round of funding to launch the Colorado National Wastewater Surveillance System Center of Excellence in August 2022. Lengsfeld and Wheeler now serve as co-directors.

“In the span of two hours, we designed this proposal with timelines and features that turned out to be highly unique and successfully funded,” Lengsfeld said. “Because of Allison’s amazing work within the state, Colorado became one of the leaders in this area.”

Now with six such centers nationwide, Colorado has emerged as a leader, she added. “We were one of the original two that were funded, so now we’re like the mama bear teaching others, and it’s been a wild, crazy, and fun ride.”

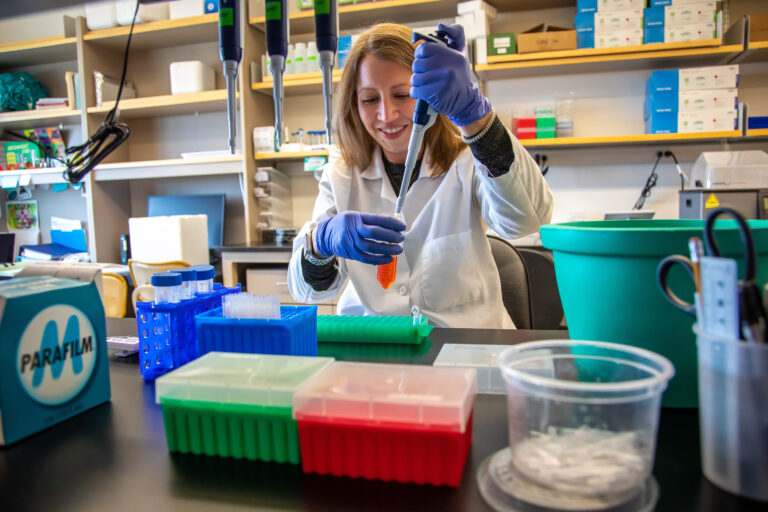

Wheeler said the DU-CDPHE partnership is an ideal collaboration. “‘We’ve been very successful as a Center of Excellence because we rely on DU for their innovation and their ability to think outside of the box,” she said. “I appreciate that innovative side that Corinne and her team bring, whereas CDPHE is more of the worker bees.” The CDPHE lab “developed the first analysis pipeline in order to sequence wastewater samples to figure out the strain of the virus circulating.”

Today, that entails getting samples delivered to the CDPHE lab via courier from 21 wastewater utilities across the state. Technicians then test the samples for COVID-19 as well as flu variants, RSV, measles, and other infectious diseases. About 40 utilities are part of a broader emergency surveillance system. The center has five part-time staffers on the DU side, and about 20 CDPHE employees are involved in wastewater surveillance.

With funding cuts potentially on the horizon, Lengsfeld and Wheeler have focused on keeping the model financially viable for the long term in Colorado and beyond by focusing on the 21 key “sentinel sites” with twice-weekly sampling and testing.

“Three years ago, we quickly realized that to reach the vision, even at the same dollar amount, there were going to have to be some drastic changes to how we made choices,” Lengsfeld said. “Colorado was the first state to move to a sustainable model in which we used sentinel sites instead of every utility to understand the state’s infectious disease behavior. The idea is to look at population density and population mobility, as well as historical disease spread, to create a risk factor, and then in each state or in each area, there would be the top sites that would demonstrate the best at capturing the overall risk.”

Added Wheeler: “We’ve built this system to be nimble and change as needed, based on what we’re seeing around the country or what we’re worried about coming into Colorado.”

Case in point: The system has successfully detected outbreaks of Enterovirus D68 (EV-D68) in metro Denver. “Now we do this surveillance each year, May through November, and it really helps our Children’s Hospital colleagues to prepare for when we might see another increase,” Wheeler said

Also, in August 2025, tests indicated an increasing viral concentration of measles in Mesa County, and the center alerted local health care providers. “Sure enough, two days later, they detected their first clinical case, and since then, they’ve had a total of 11 cases of measles in their community,” Wheeler said.

Melissa Mimna, laboratory manager at the Boulder Water Resource Recovery Facility, began working with Lengsfeld and Wheeler in 2020. “At the very beginning of the pandemic, we were seeing at least a seven-day heads-up in wastewater data compared to clinical data, so we were seeing it before anyone else,” Mimna said. “We really did see the value from the very beginning.”

Mimna said the program is financially viable for utilities, and that’s key to its long-term success. “We don’t pay for anything,” she said. “The only thing we really have to do is take the sample that we would collect anyway for regulatory reasons, pour it into the containers that they’ve sent us, put it in the kit, and put it in the pickup spot, and their courier comes and gets it. They couldn’t make it any easier for us. … I’m very hopeful that this continues and we can make it work.”

Lengsfeld said she’s optimistic that the sentinel model can withstand budget crunches and other economic turbulence. “We got a lot of flak in that first year when we did that [implemented a sentinel model],” she said. “A lot of people thought we were maybe crazy. Then we began to do the math: To sustain a national presence of understanding disease states, the nation has to move to a sentinel model.

“We have been sharing this with the CDC and anybody that will listen, essentially because we’re pretty passionate that this is a technology that is a cost-effective answer, but we need to know where to deploy to get maximum or optimal effectiveness.”

To pave the way for broader adoption, the center is releasing a training webinar in early 2026. “Our next step is to test it out in two other states as a part of our validation process, and then we would be ready, we think, to move to all of the states,” Lengsfeld said.