DENVER — The speed of evolution can vary widely from species to species. Some adaptations require millennia to emerge, while others unfold over a few years.

Robin Tinghitella, associate professor of biological sciences at the University of Denver, has made this concept the centerpiece of her research by investigating the changing songs of Pacific field crickets in response to the arrival of invasive parasitoid flies.

“I actually started working on these crickets in Hawaii when I was in graduate school,” Tinghitella said. “So I’ve been working there for more than 20 years at this point, and was interested in similar questions they’re asking about how hosts and their parasites interact, and getting really interested in questions about rapid evolution and how ecology on islands is different from in other circumstances.”

The flies came to Hawaii about 30 years ago, but the crickets have been there for about 1,600 years. “The two only co-occur in the Hawaiian Islands, and the way that the fly finds its cricket host is using the songs that male crickets sing to attract females,” Tinghitella said. “We’ve made a series of discoveries about evolutionary change in the song that these male crickets are singing in Hawaii that allows them to avoid parasitism, so we’ve gotten sucked into tracking rapid evolution in real time.”

It all began when Tinghitella was involved in the discovery of songless crickets as a graduate student, circa 2005.

“I went to Hawaii for the first time with my adviser, and we discovered that the males on one island had actually gone mute,” she said. “The wings are what they use to produce sound, and they had a wing mutation that eliminated the structures on the wing that are used to produce songs. These males would rub their wings together, but no sound actually came out. That was fantastic from the perspective of avoiding parasites, because if you can’t produce sound, the fly can’t find you. But it also poses this huge problem for locating mates, because sound is also how they attract females.”

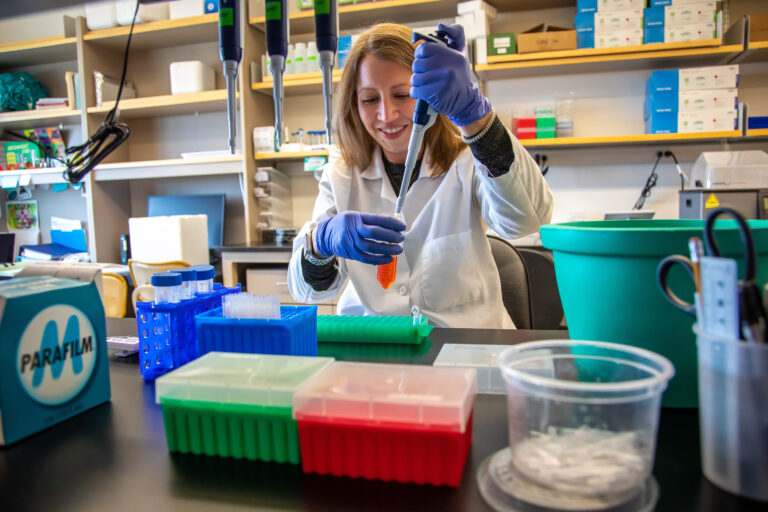

Tinghitella continued on this line of research in her postdoctoral work for a few years, the same time frame she established the Tinghitella Lab at DU, which now includes six faculty members and about 25 students. She returned to studying crickets after the “serendipitous” 2017 recording of “a brand-new song” from another population of crickets in Hawaii.

“I made an unexpected discovery that there was yet another genetic mutation that caused them to create the sound that we called purring, actually, because it sounds a lot like a cat purring,” Tinghitella said. “That song allowed them to both avoid parasites, but still attract females, so it was a better solution than silence, because it still allowed them to attract and convince females to meet with them. We’re finding more and more of these quieting mutations that change the song, but don’t eliminate it completely.”

The discovery catalyzed a longitudinal tracking project at six sites in Hawaii. “We go back to all six of those once or twice a year and do the same studies every time, so that we can track in real time what evolutionary change is happening,” she said. The research has uncovered other new songs, including one that sounds like miniature maracas and another that’s akin to a muffled normal song.

The team also tracks a control group of crickets in French Polynesia and Australia as “control locations,” Tinghitella said. “That parasitic fly has not made it to either of those places, so you have untouched cricket populations that serve as the validity that the rapid evolution happening in Hawaii is in response to the fly specifically.”

Some of her lab’s latest research has found that the flies are also rapidly evolving in Hawaii. “The flies are actually getting better at hearing and locating males [with new songs], which means that they may be able to keep up with this sort of super rapid pace of evolution that the crickets are really well known for,” Tinghitella said. “We could be one of the first labs to ever catch co-evolution in action, where both the host and the parasite are responding to each other through evolutionary change, in real time.”

Other lines of research look at the evolutionary impact of human-caused changes to the environment, such as streetlights and traffic noise. “What does it mean for evolution and can animals keep pace with the rates of environmental change that we’re imposing on them?” Tinghitella said. “What we really study is the mechanisms that organisms use to respond to change that humans cause on contemporary timescales.”

She added, “We think of those processes that Darwin was talking about as being really, really long-term processes, but rapid evolution that we can observe within the lifetime of a researcher illustrates that that’s not always the case.”

Dale Broder worked with Tinghitella as a postdoctoral fellow at DU from 2016 to 2018 and then as a research scientist in her lab from 2021 to 2024. Broder continues to collaborate with Tinghitella as an assistant professor of biology at American University in Washington, D.C.

For evolutionary scientists, the research offers a rare opportunity. “Generally, we’re looking back in time at signals that have already become important,” Broder said. “For instance, Darwin was looking at these finches who have already speciated.”

However, behaviors “are the types of traits that can only be observed in real time,” she added. “We’ve already seen such cool things. We saw a cricket morph, we tracked its emergence, and now we have noted that it’s gone. . . . That little evolutionary blip, evolutionary dead ends. There’d be no record of it if we weren’t watching it.”

Broder said her relationship with Tinghitella has been key to her career in science. “I feel so lucky to have met her, because she is one of my best friends and my favorite person to work with on anything,” she said. “We’re both super interested in communication and training of students and mentorship and trying to improve our own mentorship skills. … We’re always learning from each other and inspiring each other because we have such similar interests.”

Tinghitella said research in Hawaii also sweetened the deal. “It’s not the worst,” she said with a laugh. “Sometimes, we make not-so-awesome career decisions. That was a good one.”